Table of Contents

- Introducing Jupiter and the Jupuary Appeal Process

- The Challenge

- Implementation

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Fun Technical Details

Introducing Jupiter and the Jupuary Appeal Process

Jupiter recently hosted their annual Jupuary event—a massive celebration where JUP tokens worth hundreds of millions of dollars were to be shared with active, genuine users. The problem, as usual, was sybils, groups of fake accounts (often thousands at a time!) created by bad actors to take extra tokens.

To keep things fair, Jupiter worked with Ricardo de Arruda to turn on anti-bot measures, detecting over a hundred thousand accounts that seemed to be part of sybil clusters — but in that process, they accidentally flagged some real users as fakes. (Talk about a bouncer with an attitude!) No worries, though — Jupiter sorted it out with an appeal process powered by ZK Email.

The Challenge

Traditional airdrop verification methods often require users to share personal details such as email addresses, logins, names, or even full KYCs, that can be linked to their on-chain wallets. In Jupuary’s case, this meant that genuine users mistakenly flagged as sybils would have to expose sensitive data to reclaim their eligibility.

This not only risked user privacy, but also added friction to the appeal process. We recently made a post on how ZK Email makes airdrop verification more seamless — and we deployed exactly those ideas to solve this problem.

Implementation

The idea was that a user could either prove they had a centralized exchange account i.e. a verified Binance or Coinbase account, or they could prove they took two ‘human-like’ actions, for instance ordering on Amazon or riding in an Uber.

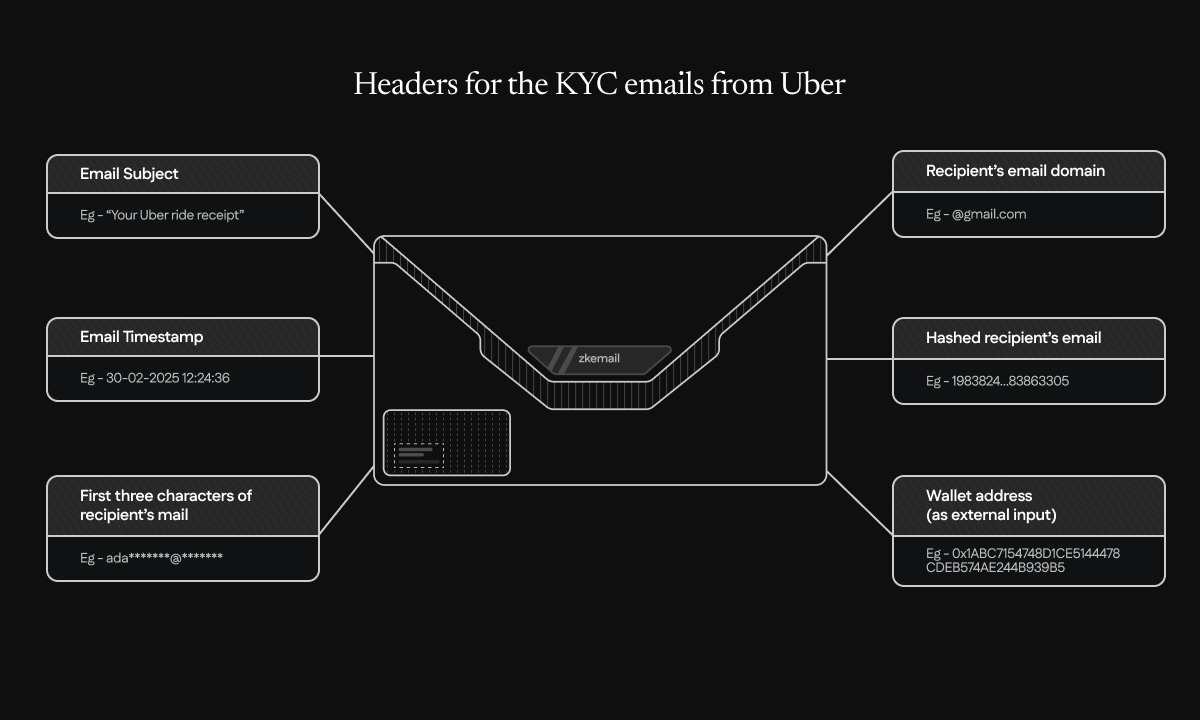

To preserve user privacy while ensuring Jupiter can verify legitimate claims, we defined a standardized structure for what information should be revealed from an email provided by the user:

- Email Subject

- Email Timestamp (the goal of this parameter was to cutoff the date, and many emails were excluded because they did not meet this requirement)

- First three characters of the recipient’s email (this helped to identify potential duplicate claims without relying on exact email matches to maintain privacy)

- Recipient’s email domain

- Hashed recipient’s email (this is still not perfect but it is good enough as the proofs were not submitted on-chain)

- Wallet address (as external input)

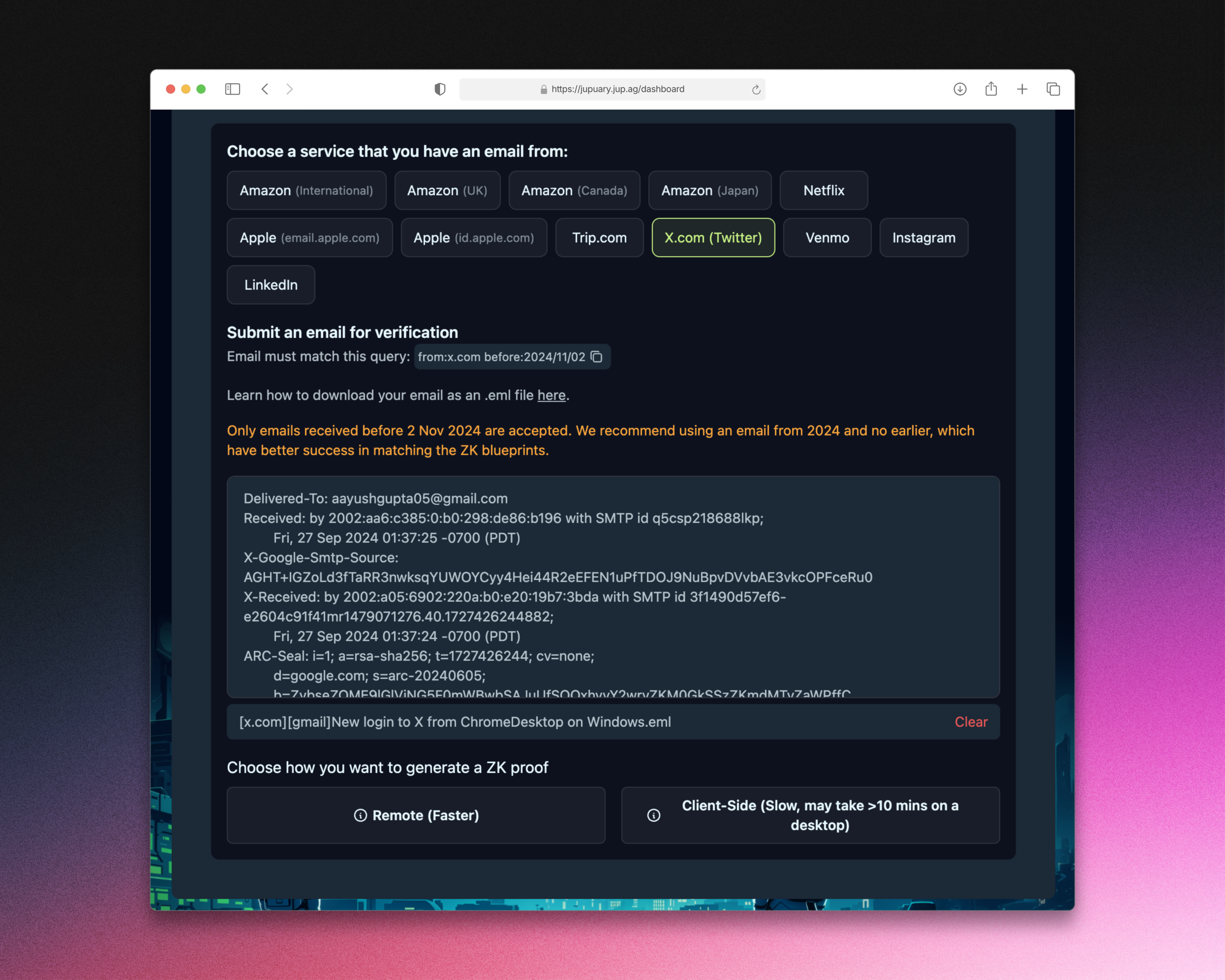

With this in mind, we created blueprints in our Registry, by defining regex patterns for each possible email format, that determined what information is revealed and what remains private. Jupiter could then just implement a handful of lines on their frontend with our Blueprint SDK, in order to use the ZK Email proofs in production!

Conclusion

By implementing ZK Email for Jupuary, we enhanced security, preserved privacy, and streamlined the appeal process. In the end, over the course of about 6 weeks, 5,800 proofs were successfully generated—4,320 remote and an estimated 1,495 local proofs. From the 160,000 wallets flagged and whitelisted for appeal, only 5,300 successfully proved they were legitimate users. Based on proof activity and clustering patterns, we estimate that between 500 and 1,700 unique sybil clusters attempted to bypass the system using similar or reused email credentials.

Appendix: Fun Technical Details

There was a lot of nuance in how we defined regexes and how we fixed edge cases to make the launch a success, while ensuring hackers could not get around the restrictions. We challenge hackers to break these! If you can, email your exploit to support@zk.email for a bug bounty pending verification.

Example: Regex for Extracting Email Recipient’s First Three Characters

With this pattern we are defining 3 parts where we only expose the middle one by setting "isPublic": true which corresponds to the yellow part in this example:

To: exa

"parts": [

{

"isPublic": false,

"regexDef": "(^|\r\n)(to:)([^<\r\n]*?<?)?"

},

{

"isPublic": true,

"regexDef": "([A-Za-z0-9!#$%&'*+=?\\-\\^_`{|}~.\/@]{3})"

},

{

"isPublic": false,

"regexDef": "[^@]*@[a-zA-Z0-9.-]+>?\r\n"

}

]

Example: Regex for Extracting Email Recipient’s Domain

In this pattern we are exposing only the domain by setting all of the parts that match everything before the @ to private and then setting all of the chars before the optional > or before a new line, you can check this example:

To: example@domain.com

"parts": [

{

"isPublic": false,

"regexDef": "(\r\n|^)to:"

},

{

"isPublic": false,

"regexDef": "([^<\r\n]*?\s*)?<?[^@]+@"

},

{

"isPublic": true,

"regexDef": "[a-zA-Z0-9_\.-]+"

},

{

"isPublic": false,

"regexDef": ">?\r\n"

}

]

Using these blueprints, Jupiter integrated ZK Email into their application using our SDK, enabling users to generate proofs using multiple verification blueprints depending on the service they opt to use. Check out an example of proving your X account here.

Edge Cases

These are a bit more in the weeds — some issues were reported by early users, and here’s how we fixed all of them within a few days of launch.

Variability in "To" Field Formatting

Parsing the "To" field presented challenges due to different email formats:

To: example@domain.com

To: Example Name <example@domain.com>

To: <example@domain.com>

A simple approach, like searching for the @ symbol, worked for To: example@domain.com but failed in cases where names were included like To: Example Name <example@domain.com> or when emails were wrapped in brackets To: <example@domain.com>.

A regex pattern such as from:[^<]+<?[^@<>]+@[^<>;"]+>?"?;\r\n could have solved this, but the optional < - <? - created a shared edge in the DFA (Deterministic Finite Automaton). This incompatibility with the current zk-regex implementation was also noted in our docs. We resolved this by identifying the standard format used by each email sender for the 'To' field and defining the optimal regex pattern for each case.

ProtonMail Body Hash Verification Issues

ProtonMail verifies the DKIM signature (which includes the body hash) on their servers for incoming external emails. After verification, they encrypt the email and deliver only the decrypted content to the user’s client (e.g., web browser or app). In addition, for non-repudiation, they strip critical randomness from the email body such that users cannot verify the email bodies themselves. We don’t think this supports user autonomy to verify their own inbox themselves, but it’s a design choice that Proton made.

Since ProtonMail does not provide access to the original email body, users cannot verify the email bodies themselves. As our blueprint verification was based only on email headers, it was easy to skip the body hash check for ProtonMail users.

Issues with Yahoo Email Export

Yahoo users faced difficulties downloading their emails as .eml files. Even when they succeeded, their proof generation failed due to the absence of the DKIM-Signature field in the email headers. For this issue we provided a workaround for these users to import their yahoo account to an Outlook client, and they were able to successfully complete their appeal process.

If you’re excited to use ZK Email for your own organization’s verification processes, reach out to support@zk.email and we’d love to get you set up!